Expanding Great Lakes Trade

What’s Changed Since 1995?

There are a few reasons why the canal should be reconsidered today. Since the last failed attempt in 1995, the area has undergone a transformation that has brought about several new opportunities that may benefit from a canal. In the past 30 years, new industries in northeast Ohio and western Pennsylvania have been expanding to take the place of the declining steel industry. Beginning in 2005, the Utica and Marcellus oil shale fields emerged, and the polymer business grew dramatically. In 2022, Shell Polymers built a world-class polyethylene pellet plant in Monaca, Pennsylvania, at the point where the canal would join the Ohio River. The proposed Nippon Steel purchase of US Steel, which is expected to be finalized this year, might revitalize the steel industry, making the canal a potential iron ore route from the Great Lakes. Further, international container shipments have grown dramatically throughout the United States. Container services are now expanding directly into the Great Lakes, along with other potential new business opportunities.

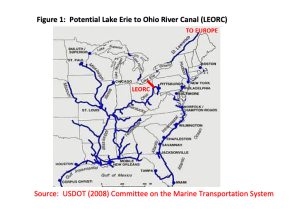

More generally, water temperatures in Lake Erie and the Great Lakes have increased, and ice coverage during the winter continues to decrease, allowing the seaway to remain open longer than in past years. These factors, along with favorable economics of water transport, are increasing commerce on the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway. In addition to the regularly scheduled container service between Cleveland, Ohio, and Antwerp, Belgium, initiated in 2014, and the new regularly scheduled container service between Duluth, Minnesota, and Antwerp, the Port of Indiana recently announced that it is developing an international container port at Burns Harbor. Furthermore, Monroe, Michigan, is considering shipping automobiles to Europe by water. Hamilton, Ontario,; Windsor, Ontario, and Detroit, Michigan, are also considering new container services. Using the proposed canal, Pittsburgh might also benefit from a direct container service to Europe that bypasses East Coast ports.

New Business Opportunities

There are several candidates that might benefit from access to the proposed new canal.

- Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, is on the Ohio River at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers. Greater Pittsburgh, with a population of 2.4 million accesses the Gulf of Mexico via the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, but it cannot access the Atlantic Ocean directly by water. As such, breakbulk and containers between Pittsburgh and Europe are routed by overland transportation through East Coast cities. The canal would give Pittsburgh direct water access to Great Lakes cities and Europe via the seaway. Since the Port of Cleveland continues to successfully operate its container service with Antwerp, a similar service would likely be favorable for Pittsburgh.

- Though diminished, the steel industry is active, especially along the Monongahela River near Pittsburgh. For many years the steel industry supported a canal to Lake Erie to receive iron ore by water. Companies may still be interested. Steel fabricators in the Youngstown/Pittsburgh area may be able to receive specialty steel coils and bars economically from Europe by water, as do Great Lakes cities. This would reduce their need for costly overland transportation from East Coast ports.

- The proposed canal passes through the center of the Marcellus and Utica shale oil fields and could deliver oil field equipment and supplies, as well as ship crude oil and other products by water, bypassing more expensive overland transport.

- Ethylene gas from the Marcellus and Utica shale oil fields is processed into polyethylene pellets at the Shell Polymers plant, which opened in November 2022 in Monaca on the Ohio River. Monaca is at the origin of the proposed lake to river canal. Shell Polymers and its many customers might benefit from shipping by water rather than overland transport. IHS Markit (2017) predicted a need for four additional plants the size of Shell Polymers’ to process the forecast growth in the Marcellus and Utica fields.

- The region west of Monaca is known as the “polymer valley” since it hosts more than 1,200 polymers and materials companies. The canal would connect these companies with Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway and European cities by water.

- Marathon operates a world-class 291MBD refinery on the Ohio River not far from the proposed canal, in Catlettsburg, Kentucky. Marathon has one of the largest tank barge fleets on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. A canal would give the company waterborne access to U.S. and Canadian Great Lakes cities as well.

Economic and Environmental Benefits

Water transport is inherently more fuel efficient and generates considerably lower greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions than rail or truck. The Research and Transportation Group (2013) compared the fuel efficiency of seaway-sized vessels with rail and truck and determined that “the seaway-sized fleet can move its cargo 24 percent farther (or is 24 percent more fuel efficient) than rail and 531 percent farther (or is 531 percent more efficient) than truck.”

Furthermore, with upcoming regulations and renewals, these percentages increase to 74 percent and 704 percent farther than rail and truck, respectively. The study also determined that GHG emissions are also lowest for the seaway-sized vessels, with rail and truck emitting 22 percent and 550 percent more, respectively, when carrying 1 ton of cargo 1 mile. Upcoming regulations and renewals increase these percentages to 72 percent and 712 percent, respectively, per the Research and Transportation Group study. A United States Department of Transportation study (2019) of U.S. river barge versus rail and truck yielded similar results.

In an era of high fuel costs, fuel efficiency makes water transport more economic than rail and truck. Similarly, in an era where global warming is a major world problem, and where the transportation industry is a major contributor to global warming, converting from the higher emissions of rail and truck to the lower emissions of water transport is an important part of the solution.

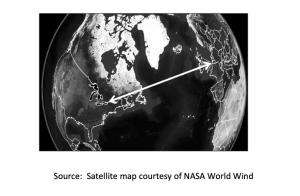

Specific to the proposed canal, two additional factors contribute to saving fuel and emissions. First, the seaway is the shortest route to the Midwest from the trading centers of Europe, saving distance, fuel and emissions. These trading centers currently channel large volumes of European, Middle Eastern and Asian products to the U.S. East Coast ports. See Figure 2 (Hull 2012). Adding cities such as Pittsburgh to the St. Lawrence route includes them in this most direct fuel-efficient route. Having canal access would be an easy way for Pittsburgh to pick up on a missed opportunity.

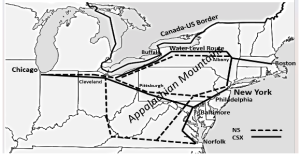

The second factor regards the Appalachian Mountains, which pose a significant barrier to efficient movement of goods between Midwestern cities and the East Coast ports they utilize for imports and exports (Hull 2012) as is seen in Figure 3a. Crossing the Appalachians by rail requires circuitous routes and elevation changes as seen in Figure 3b, a schematic of some main railroad routes. As example, the CSX “water level route” between Chicago and the Port of New York/New Jersey heads east from Chicago, then northeast from Cleveland, skirting the south shore of the Great Lakes to Buffalo, then runs due east along the old Erie Canal to Albany, and finally turns due south along the Hudson River to New York City. Circuitous routes, such as the water level route, and elevation changes entail greater fuel consumption and emissions generation. This further highlights the advantages of the straight-line St. Lawrence route, also shown in Figure 3a. Using calculations from searates.com, the all–water route from Rotterdam to Cleveland is 4,000 miles and takes 11 days, while the same route through New York City is 3,800 miles by water and 467 miles by the water level route, for a total of 4,267 miles. The time is 13 to 20 days by water due to stops at multiple East Coast ports, plus waiting time at the congested Port of New York, plus one to three days of rail time. Thus, the St. Lawrence route is both shorter and considerably faster.

Social and Safety Benefits

A canal connecting the Ohio River to Lake Erie has the potential to revitalize the area of Appalachia that includes eastern Ohio, western Pennsylvania and parts of West Virginia along the Ohio and Monongahela rivers. This area has faced declining coal and steel industries since the 1970s, with Youngstown alone losing 50,000 jobs (out of a population of 150,000) between 1977 and 1982. In contrast, U.S. ports are “engines of job creation” with every $1 billion in exports from American seaports creating 15,000 jobs (Association of American Port Authorities 2018). The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway alone supports 241,000 jobs (Martin Associates 2023).

Further, water transportation is considerably safer than rail. In February 2023, an NS Railroad train derailed 38 hazardous material cars in East Palestine, Ohio, near the proposed canal route, causing much of the town’s 5,000 residents to be evacuated. The hazardous waste cleanup is ongoing. Another example is the Lac Megantic 73 hazardous materials car derailment in July 2013, which destroyed 70 buildings in the downtown area of Lac Megantic, Quebec, resulting in 43 casualties.

In contrast, water has an impressive safety record, with rail having 21.9 times as many fatalities per million ton-miles as barge, and truck having 79.3 times as many fatalities as barge (USDOT 2019). Further, one seaway-sized vessel carrying 30,000 tons of cargo would replace either 301 rail cars or 963 trucks from overland traffic (Research and Traffic Group, 2013), reducing congestion and the chances of overland accidents. Switching cargo from overland transport to water reduces the likelihood of such tragic events.

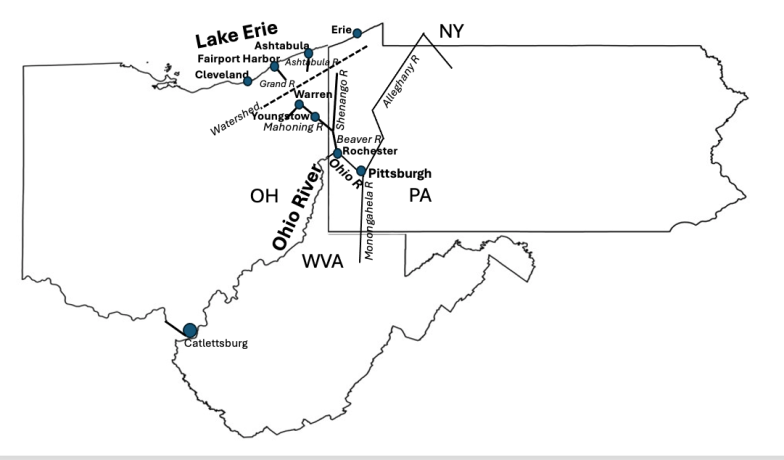

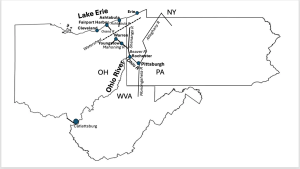

Routes Along the Proposed Canal

The proposed canal would create a continuous water “highway” crossing between the Ohio River and Lake Erie watersheds. An artificial lake, reservoir or other source of water would be required near the “summit” between the two watersheds to ensure a consistent depth of water throughout the canal. The dividing line between the watersheds is shown by the dashed line in Figure 4.

Many routes for the canal have been proposed over the years (USACE 1995). Most of the proposed routes begin at Rochester, Pennsylvania, and end at either Fairport Harbor, Ohio; Geneva, Ohio; Ashtabula, Ohio; or Erie, Pennsylvania. Proposed routes are included below.

- The Ohio River originates in Pittsburgh at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers. From Pittsburgh, the Ohio River flows northwest to Rochester, where it veers sharply southwest and away from the lake. Rochester is approximately 100 miles from Ashtabula, one of the Lake Erie ports nearest Rochester.

- The Mahoning River flows south from northeast Ohio through the Ohio River watershed past Warren and Youngstown, joining the Beaver River, at New Castle, Pennsylvania. Similarly, the Shenango River flows south through Pennsylvania to the Beaver River in New Castle. The Beaver River joins the Ohio River at Rochester.

- The Ashtabula and Grand rivers flow north across the Lake Erie watershed to cities such as Ashtabula, Fairport Harbor, Geneva or potentially others. Canalizing these rivers along with the Beaver, Mahoning and/or Shenango connects the Ohio River and Lake Erie.

Next Steps

Actionable next steps toward developing a new canal start with identifying the stakeholders, gauging their interest and developing detailed economics. Stakeholders would include regional economic development agencies, such as TEAM NEO in Ohio, TEAM PA in Pennsylvania, the Pittsburgh Chamber of Commerce and involved ports, such as the Port of Pittsburgh and local Lake Erie ports. Industry stakeholders would include Marathon Oil, Shell Polymers, US Steel and steel fabricators such as Tata Steel of Warren, Ohio, and Vallourec Star in Youngstown, Ohio. It would be important that this project addresses both Ohio and Pennsylvania interests, since any canal route chosen runs close to the border between the states, and shippers from both states would benefit from it.

Ports are known as “engines of job creation” since they support manufacturing, distribution and transportation jobs, and their access to water attracts new businesses. A busy Lake Erie to Ohio River canal could revitalize eastern Ohio, western Pennsylvania and parts of West Virginia. Cargo moving on a busy canal would otherwise move by roads and railroads, at substantial cost and emissions savings. The emissions reductions would contribute to a reduction in global warming, a major environmental goal.

Bradley Hull, PhD, is associate professor emeritus at John Carroll University in Cleveland, Ohio. He can be reached at bzhull@jcu.edu.

Editor’s Note: Special thanks to the historical contributions of Ronald D. Reid C.E., who was involved in the 1995 project; Michael Riley, president of the American Canal Society; Roy Knapp of Consultech; and Vince Guerrieri of the Elyria-Chronicle Telegram.

References

Aley, H. (1975) A Heritage to Share: The Bicentennial History of Youngstown and the Mahoning Valley. The Bicentennial Commission of Youngstown and Mahoning County.

Association of American Port Authorities (2018). https://www.aapa-ports.org/advocating/content.aspx?ItemNumber=21150 last accessed 3/33/2024.

de Greet, J. (1965) Akron Beacon Journal. August 22, Sunday Magazine, Section E, page 1.

Great Lakes Seaway Review. (2009) Timeline Great Lakes/St Lawrence Seaway. 50 Years — Celebrating the Great Lakes/St Lawrence Seaway System. January-March. Harbor House Publishers. Boyne City, MI.

Guerrieri, V. (2019) “Mike’s Big Ditch”. Belt Magazine. August 28. (https://beltmag.com/kirwan-canal-lake-erie-ohio-river/).

Hull, B. (2012) “The Chicago-East Coast Corridor: Changing Intermodal Patterns” Transportation Journal. 51 (2), pp. 220–237.

IHS Markit (2017) Prospects to Enhance Pennsylvania’s Opportunities in Petrochemical Manufacturing. Prepared for Pennsylvania Department of Community & Economic Development. https://teampa.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Prospects_to_Enhance_PAs_Opportunities_in_Petrochemical_Mfng_Report_21March2017.pdf

Martin Associates. (2023) Economic Impacts of Maritime Shipping in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Region. July. Lancaster PA. (https://www.greatlakesports.org/resource-types/economic-impacts/)

Patterson, B. (1919) “Lake Erie and Ohio Canal in a Great Waterways System.” Mississippi Valley Magazine, October. pp. 6-12.

Reid, R. (1984) “Two Hundred Years of Water Transportation in Eastern Ohio and Western Pennsylvania.” Western Pennsylvania Genealogical Society, Vol 10, No 3, February.

Reid, R. (1995) “The Canal Heritage of Youngstown.”, Towpaths. Vol 20. No. 1 & 3. Canal Society of Ohio.

Research and Traffic Group (2013) Environmental and Social Impacts of Marine Transport in the Great Lakes- St. Lawrence Seaway Region. January.

USACE Pittsburgh Division. (1995) Lake Erie – Ohio River Canal: Ohio and Pennsylvania Reconnaissance Report. March.

USDOT. (2019) Short Sea Shipping: Rebuilding America’s Maritime Industry. Statement of Mark Buzby, Administrator Maritime Administration, USDOT before the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure US House of Representatives. (https://www.transportation.gov/testimony/short-sea-shipping-rebuilding-america%E2%80%99s-maritime-industry)

USDOT (2008). Committee on the Marine Transportation System, National Strategy for the Marine Transportation System: A Framework for Action (https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/38099)

Seaway System Closes for 2025 Navigation Season

The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway System officially closed for the 2025 navigation season on January 12. The system was supposed to close on January 5, but ice buildup created shipping... Read More

Toledo Harbor Dredging Completed

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Buffalo District recently completed the largest annual dredging project on the Great Lakes. Dredging of Toledo Harbor’s federal navigation channel began in the fall and wrapped... Read More