Protecting Great Lakes Waters

Lake Erie Gets High Level Attention

Lake Erie is receiving top-level attention on a number of fronts. Federal, state and local officials have policy initiatives and programs to benefit the Lake’s ecology and its social and cultural resources. Here’s a closer look at four initiatives currently being addressed to protect Lake Erie.

A Pollution Diet

“There’s reason to hope that, in time, the Maumee River will no longer display, as it has for countless summers, a loathsome foul and slimy green surface as it flows through Toledo on to Lake Erie’s Western Basin,” said Judge James G. Carr, United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio.

Judge Carr’s rather tempered optimism is part of a consent decree signed in May, a document that hopefully starts, after almost six years of back-and-forth litigation, to limit and even prevent harmful algal blooms (HABs) in the Maumee River. HABs can produce toxic compounds. In 2014 Toledo shut its drinking water intakes because of HAB cyanotoxins.

The consent decree requires the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (Ohio EPA) to develop a plan that will decrease pollution into the Maumee River and then into Lake Erie. Algae thrives in the Lake’s shallow western basin, particularly during warm and tepid conditions. Phosphorus is a key algal nutrient and of central concern. Phosphorus can come from numerous sources, sewage treatment plants, for example, or industrial facilities, and, importantly, from agricultural feedlots and manure and fertilizer applications. Many environmental groups charge that phosphorus from manure, particularly CAFOs – “concentrated animal feeding operations” – are largely to blame.

Livestock farmers push back. Duane Stateler is a fifth-generation pig farmer from McComb, Ohio. Stateler, in response to questions sent via the Ohio Pork Council, emphasized that his farm and over 96% of other Ohio farms are family operations that take stewardship of animals and land very personally.

He noted that for manure application, Ohio is the most heavily regulated state, requiring a comprehensive manure management plan that is updated and audited by a third party. He said Ohio’s phosphorus TMDL is the most science-based of its kind in the country. He added that western Ohio’s farmland would benefit from more manure fertilizer because then farmers would not have to depend on synthetic fertilizers.

The Consent Decree requires the Ohio EPA to develop a “Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) Plan” to (1) keep pollutants below harmful levels and (2) reduce pollution. The Maumee River basin includes Indiana and Michigan, regions beyond Ohio’s authority. A TMDL plan does not set new regulatory requirements, like an industrial discharge permit. The federal Clean Water Act does not regulate agricultural operations as it does industrial and municipal wastewater treatment facilities.

The U.S. EPA had to approve Ohio EPA’s TMDL plan by July 30, although a 90-day extension is possible. Importantly, in January 2023, the U.S. EPA released a “Effluent Guidelines Program Plan,” a starting point for a national, detailed review of CAFOs and impacts. The EPA hopes to start this work by year’s end. Developments in Ohio could be part of a broader, national initiative.

For implementation, Ohio EPA’s TMDL plan takes an all-of-government approach. Multiple Ohio agencies will strengthen existing water quality plans, such as working through H2Ohio, a program with a singular focus on phosphorus reduction and preventing algal blooms.

Ohio EPA said that H2Ohio has already started “the long-term process to reduce phosphorus runoff from farms through the use of proven, science-based nutrient management best practices and the creation of phosphorus-filtering wetlands.” H2Ohio participants include the Departments of Agriculture, Natural Resources, EPA and the Lake Erie Commission, which includes directors from all of those agencies. An Ohio EPA spokesman said that “as an outcome of the TMDL, Ohio EPA will lead the phosphorus reduction goals evaluation process, reviewing efforts being made by the Ohio agencies, along with actions from other key partners.”

U.S. EPA’s Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI) is another important driver. The Maumee watershed is a priority region and continued GLRI programs, with 5-year action plans, will maintain and expand prevention and control strategies.

Additionally, Ohio EPA has a new “watershed-wide general permit” that expands phosphorous controls on 39 facilities, i.e., controls beyond reductions required by existing permits.

Taken together, Ohio EPA’s TMDL plan is expected to stop Lake Erie’s episodes of green slime. Meanwhile, on August 1, the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers (USACE) announced availability of a demonstration program designed to treat and prevent harmful algal blooms, at least within USACE projects, including the Great Lakes. This demo program is required by Section 128 of WRDA 2020. The Corps was soliciting public comments on the merit of its draft document through August31.

Lake Erie Islands

The Maumee River at Toledo, from the Maumee-Perrysburg Bridge to Maumee Bay does not meet even minimum Ohio EPA standards for fish habitat, fish communities and benthic communities (bottom and near-bottom organisms).

Now, a project overseen by the Toledo-Lucas County Port Authority (TLCPA) hopes to help change those dismal water quality numbers. The Port – along with an array of partner agencies, including the City of Toledo, Maumee Area of Concern Advisory Committee, Ohio Department of Natural Resources, and Ohio EPA – is ready to start the restoration of two river islands – Delaware/Horseshoe Island and Clark Island, both owned by the city of Toledo. The islands, about nine miles south of Lake Erie, have been degraded over the decades but once rehabilitated, will take on new ecological significance, helping both the Maumee River and Lake Erie.

During the last 80 years the two islands have literally shrunk because of many factors: erosion from sand and gravel mining, modified river flows, frequent floods and high Great Lakes water levels. Delaware/Horseshoe lost 34 acres, over 39% of its upland area since 1963. Clark Island has almost disappeared: just 4.7% remains of its 1940 footprint, an estimated loss of over 28 acres.

Joseph Cappel is vice president of business development with TLCPA and a project leader. Cappel said that development funding has come from two sources. H2Ohio provided a $620,000 grant. H2Ohio was initiated by Ohio Governor Mike DeWine in 2019 and has a critical focus on reducing nutrient inputs into Lake Erie that cause harmful algal blooms. The second is a federal Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI) grant for $320,000.

Project work includes:

- Rock revetments to protect newly rehabilitated areas from river flows, boat wakes and ice scour;

- Extensive wetland restoration;

- Shorelines contoured to varying depths, enhancing habitats;

- Stone and wood structures added to slow water flows and promote sedimentation;

- Restoring natural water flows over and around the islands to prevent erosion.

“The project team had a diligent focus on designing the island improvements to maximize nutrient reduction opportunities,” Cappel said. “Significant modeling and design adjustments were made to determine the best location of inlets, outlets and interior island areas to encourage calm waters for sediments to settle from the water column.”

These efforts are expected to remove up to eight metric tons of total phosphorus and 60 metric tons of total nitrogen over the useful life of the project, about 15-25 years, dependent on water levels and other variables. Cappel said the project can be replicated at other Great Lakes sites. “The concepts and design elements are definitely transferable in any tributary where the same benefits of nutrient reduction and habitat creation are sought,” he said.

Cappel added that Metroparks Toledo has a similar GLRI-funded project at Audubon Island, upriver from the Port’s project.

Project permitting has been extensive, including federal, state, tribal and local agencies. A mussel survey is still incomplete. However, Cappel said the project was shovel ready in June, with the total cost being about $13 million. Construction funds are expected from H2Ohio and GLRI.

Marine Sanctuary Designation

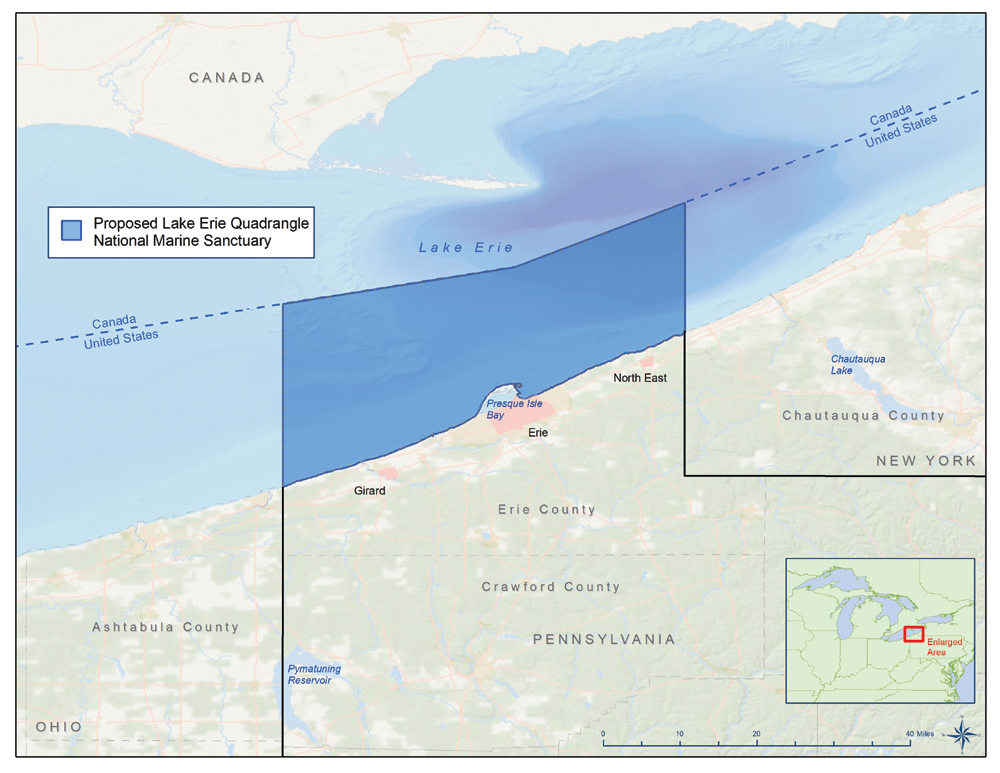

On May 19 NOAA published a notice of intent (NOI) to designate a “Lake Erie Quadrangle National Marine Sanctuary.”

The Notice announced NOAA’s plans to prepare a draft environmental impact statement (EIS) to analyze the impacts of a sanctuary designation. The Notice also started a public comment period that was open until July 18. NOAA will use the public comments to inform next steps. As of mid-July, there were 81 comments filed, mostly supportive of the sanctuary. NOAA’s move has a relatively long history. In December 2015, Erie County submitted a nomination seeking sanctuary status for the Lake.

NOAA writes that the Pennsylvania section of the Lake “represents a historically rich region where the long relationship between human activity and the maritime environment has created meaning and a sense of place, which is expressed and preserved in a wide variety of maritime cultural resources from sacred places and cultural practices to lighthouses and historic shipwrecks. Together, these tangible and intangible elements form a rich maritime cultural landscape.” Lake Erie was one of the busiest waterways of the mid-19th century.

To advise its upcoming work NOAA asked for comments focusing on nine topic areas:

- Boundary alternatives. As proposed, the sanctuary would cover approximately 740 square miles (1917 square kilometers). It would start at Erie County’s coastline, extend north to Canada’s border, and east-west from New York State to Ohio, about 75 miles. Erie’s Port would not be included to maintain compatible use with shipping and other commercial activities;

- The location, nature, and value of cultural and historical resources;

- Specific threats to those resources;

- Information on indigenous heritage;

- Potential socioeconomic, cultural and biological impacts resulting from designation;

- Non-regulatory actions that NOAA should prioritize;

- A regulatory framework;

- Regional economic benefits;

- A sanctuary name.

A draft EIS is expected in winter 2024, with a “record of decision” in 2025.

Buffalo Harbor Improvements

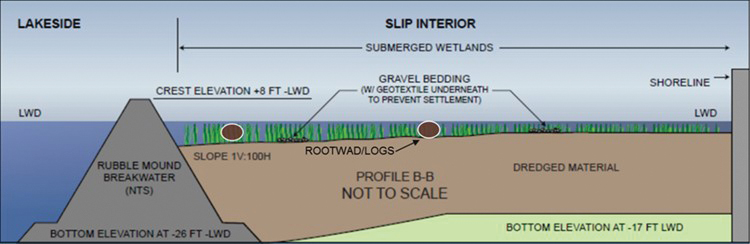

The beneficial use of dredged material is a top goal among port and waterways planners. This summer an Army Corps of Engineers (ACE) project is getting underway that will make use of dredged material from the Buffalo River, part of an important wetlands restoration project in Buffalo’s Outer Harbor. The $14.8 million project aims to reverse coastal wetland degradation in the Niagara River system and across the Great Lakes. Decades of industrial development and hardening of shorelines have diminished fish nursery and spawning habitats in these areas. Beneficial use is in contrast to just shipping and dumping dredged material somewhere else in a lake or the ocean.

In July, the ACE Buffalo District awarded a $5.3 million contract to Michigan-based Ryba Marine Construction Company to construct a stone breakwater in the abandoned Shipping Slip 3 in Buffalo’s Outer Harbor. The project is being conducted in three phases – construction of the breakwater, placement of dredged material, and formation of aquatic and sub-aquatic habitat.

“This is just the first visible step of a project that will revive the natural aquatic habitat on Buffalo’s Outer Harbor,” said Lt. Col. Colby Krug, commander of the USACE Buffalo District.

Steve Ranalli, president of the Erie Canal Harbor Development Corporation, noted that the project is directly adjacent to Wilkenson Pointe, where an extensive, two-year improvement project will start this fall. “The Slip 3 project,” Ranalli said, “will help renew key elements of the aquatic habitat that are crucial to a vibrant waterfront.”

Steve Ranalli, president of the Erie Canal Harbor Development Corporation, noted that the project is directly adjacent to Wilkenson Pointe, where an extensive, two-year improvement project will start this fall. “The Slip 3 project,” Ranalli said, “will help renew key elements of the aquatic habitat that are crucial to a vibrant waterfront.”

The project will use approximately 44,000 cubic yards of bedding, underlayer, and armor stone. The breakwater will extend across the entire mouth of the slip, with a portion submerged to allow for connectivity to the Lake and support the health of the future wetlands. Base construction is scheduled to begin this fall and be completed by November. Upper layer construction is scheduled for spring 2024.

Approximately 285,000 cubic yards of Buffalo River sediment, collected over a six-year period (an estimated three dredging cycles) will be placed in Slip 3 to create 6.7 acres of coastal wetland habitat. The next dredging cycle is scheduled for summer 2024 and will be the first to contribute material for this project. The sediment is certified as clean by state and federal standards and approved for this beneficial use.

The new habitat will also include gravel beds, rock piles, root wads, logs, and existing dock piles to provide maximum habitat complexity and structure. Planting of native species will include submerged and emergent aquatic vegetation that can compete with invasive species and provide high-quality aquatic habitat for both aquatic species and migratory/resident bird species.

Project information and safety signage will be installed along Slip 3 prior to construction to keep the public informed and help ensure safety at the site.

Plans for habitat creation at the Outer Harbor used lessons learned from previous partnership between USACE and the city of Buffalo in the first successful beneficial use project on the Great Lakes – restoring a wetland ecosystem at Unity Island. Slip 3 was identified by a multiagency committee as a habitat management opportunity in the Niagara River Area of Concern.

The feasibility study for this project was 100% federally funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI). USACE and ECHDC executed a Project Partnership Agreement in January 2022 enabling the design and implementation phase, now underway. Design and implementation are cost-shared 65% Federal (USACE) and 35% Non-Federal (ECHDC with funding from the GLRI).

Based on the current USACE construction budget, the ECHDC total commitment over the course of the project will be $4,972,000 over a 12-year period. This funding is from the New York Power Authority, through relicensing agreements tied to the operation of the Niagara Power Project.

Sea Lamprey Control Initiative Enters Five-year Implementation Phase

The Supplemental Sea Lamprey Control Initiative (SUPCON) has entered a new, five-year implementation phase following several years of successful proof-of-concept research. Funded by the Great Lakes Fishery Commission, SUPCON expands... Read More

Alliance for the Great Lakes Addresses the Impact of Data Centers

The Alliance for the Great Lakes (AGL), a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization that works to protect, conserve and restore the Great Lakes, is investigating the impact of data centers and agricultural... Read More