Salvaging History in the Great Lakes

The summer calm that comes to the Great Lakes provides the ideal conditions for tracking down the remains of the many ships that were lost when the waters were not so still. With an estimated 6,000 shipwrecks littering the floor of the Great Lakes, there is no end to what can be discovered. Leading the hunt is the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society (GLSHS), which is already planning a return to the site of last year’s top discovery of the 172-foot schooner-barge Atlanta. The ship’s remains were found 35 miles off Deer Park, Michigan, in 650 feet of water and the historical society has been anxiously awaiting the winter thaw to go take another look.

Record Number Discovered

According to Corey Adkins, communication and content director at GLSHS, while the discovery of Atlanta was a highlight, last summer his group came across a record 10 shipwrecks as it mapped 2,500 miles of Lake Superior. “Last year was a weird year for finding wrecks. We never find 10 in one year. We have identified four so far, but we have a lot more work to do this summer,” he said.

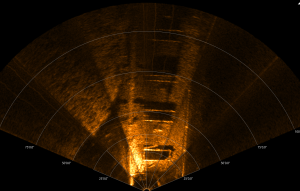

Last year’s wrecks were found through a partnership with Virginia-based Marine Sonic Technology, which allowed for the use of their towed side-scan sonar to map the seafloor. A side-scan sonar is submerged and towed by a ship across a planned grid. The sonar bounces off stationary objects sending signals up to the crew who decide if the object is of interest or just a rock. Any area that shows promise of something unique is marked for the crew to return to take another run with the sonar to try to gain a better picture of what’s beneath the surface. If the sonar shots prove interesting, a remote operated vehicle (ROV) will be deployed. The ROV can reach depths of more than 800 feet and carries high-definition cameras for a clear view of what’s below. The three to 10-man crew onboard works up to 16-hour days to take advantage of fair weather and seas. With weather patterns known to change quickly, they know time is limited, further complicated by the availability of the crew on the limited days the sun shines.

Adkins admits sometimes they find they have chased a boulder, but today’s technology is so precise that such mistakes are rare. And last summer there were no mistakes. Because so many of the wrecks lie at such extreme depths, they are often well preserved making them easy to identify. That was the case with the Atlanta, which was easily identified when the ROV returned an image of the ship’s fully intact nameplate.

But the careful preservation was not only what made this find so unique.

The Atlanta

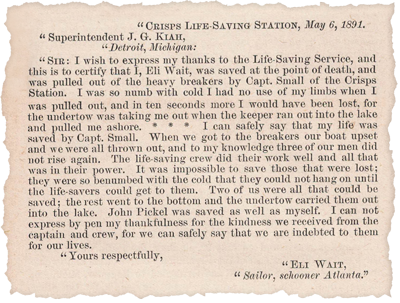

The sinking of the Atlanta was covered extensively by the media of the time. It was reported that it sank on May 4, 1891 as it was carrying a load of coal that was being towed by the steamer Wilhelm. A gale came up suddenly, snapping the towline and essentially leaving the Atlanta dead in the water. The crew was able to get to lifeboats, but the storm proved too treacherous and within sight of the Crisp Point Life-Saving Station, the boat capsized. A first-hand account of the sinking from one of the survivors, Eli Wait, was recorded by U.S. Life-Saving Service. The research team was able to verify the account by what they saw from the ROV video, including signs that the masts had been snapped off at the deck. The survivor credited the Life-Saving Service (the organization eventually became the U.S. Coast Guard) with saving his life.

The loss of a ship was nearly commonplace. During the Industrial Revolution, ships plied the waters of the Great Lakes hauling coal and iron along a route from White Fish to Grand Ray that left ships nowhere to hide when the weather turned. “Storms on the Great Lakes are like being in a washing machine with waves hitting from all sides. Ships were regularly caught in storms, or found they were in fog and collided with other ships since there was no radar. It’s estimated 30,000 lives have been lost on the lakes,” Adkins said.

- Name Board

- Ship’s Wheel

- Broken Mast

- Capstan

- Bow

- Pump

- Toilet

Museum and Organization

The GLSH was formed by a group of divers in the late 1970s who loved to dive and share what they found. They turned to the Whitefish Point Light Station, that at that time was in disrepair, as the new home to place their findings. They restored the lighthouse and the keeper quarters, which has today become the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum, and eventually, the U.S. Weather Bureau Building at the Soo Locks Park in Sault Sainte Marie came into the fold. Together, the museums host 70 to 80,000 guests annually, many of whom come to see the display of the Edmond Fitzgerald, but leave knowing much more about the history of shipwrecks.

“The museum is a peaceful place where you can go out and sit on the beach, hunt for rocks, or just look at the lake and wonder what happened out there all those years ago,” Adkins said.

While there are artifacts in place from those early dives, including the bell from the Edmund Fitzgerald, a change in Michigan law made salvaging from shipwrecks illegal without special permits, so much of today’s displays are storyboards and video. Adkins said that the depths where many wrecks sit make it nearly impossible for divers to reach the sites and removal can cause damage, so keeping all the finds intact is not only necessary, but helps to preserve the history.

The process to locate shipwrecks is not simple or cheap. Admission fees and donations, along with grant funding, provide the money needed for the exploration. But Adkins reflects that looking for and finding shipwrecks is valuable history. “It’s part of America and who we are. The wrecks we hunt are preserved time capsules. Through them and the stories, we can learn about the human spirit. There were men who lost their lives making a living to support their families and those brave men and women who went out in lifeboats to save people. Each wreck represents a time in our country and the people of that time,” he said. He also commented that they are always searching for family members of those who were lost or survivors. “If anyone has heard a conversation about how great grandad went down with the Atlanta, we’d love to speak to them and close the loop.”

Great Lakes States Receive USDA Forest Service Funding

The Forest Service has awarded $6.28 million in grants to support restoration projects on nonfederal lands in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio and Wisconsin. In all, 38 projects... Read More

Salvaging History in the Great Lakes

Tracking shipwrecks honors those lost in the lakes The summer calm that comes to the Great Lakes provides the ideal conditions for tracking down the remains of the many ships... Read More